Looking for a little diversion last night, I watched Apollo 10 1/2. I'm the same age as Richard Linklater so I could easily relate to his fascination with the space age and wanting to go up in a rocket myself. I drank Tang and ate space sticks as a kid. I had the National Geographic map of the moon on my wall. My mother had it glued to a piece of Masonite (itself a space age product) so that it could be hung from a concrete nail in the porous concrete block of our Florida home. At one point, I had learned the names of many of the craters and knew my way around the moon as well as I did any map. I imagined myself so often in space that I had dreams of weightlessness, and even ones where I floated off in space, watching the earth diminish in size until it was no more than a little speck in the cosmos, waking with a start. A friend of mine at school claimed to have a telescope that was so powerful he could see the footprints Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin left behind on the surface of the moon. None of us doubted him at the time. We were completely swept up in Apollomania.

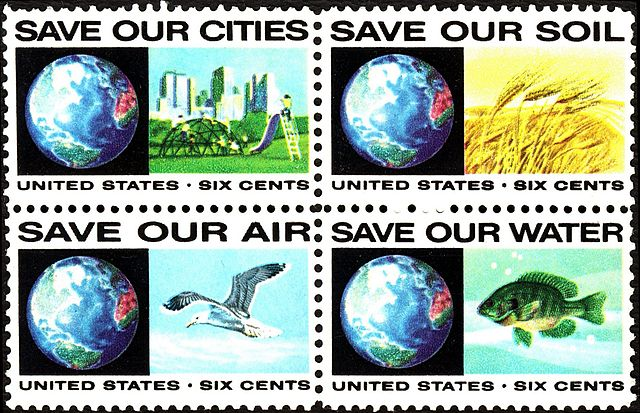

The future seemed so bright. Religious fanaticism was kept to the fringes. Politics were pretty much mainstream, as the firebrands were reduced to the fringes as well. No one doubted science, at least not publicly. I was an avid stamp collector and collected most of the US stamps from the space programs. I still have many of them.

Conspiracy theories still abound. There were those who felt that the Apollo missions were staged, but it wasn't until the end of the program in 1975 that doubt began to creep in. Slowly at first, but then more wild conspiracies began to gain currency; fueled by books like Chariots of the Gods and television shows like In Search Of, hosted by Leonard Nimoy. They had us imagining early astronauts building the Egyptian pyramids and all sorts of strange things happening in the Bermuda Triangle. It was pretty hard not believing some of these stories, at least in part, because an active imagination could take you almost anywhere.

By the mid 70s, the United States and the world had fallen into a deep recession, due in large part to escalating fuel prices. President Jimmy Carter was asking us to turn down our thermostats and wear sweaters, drive 55, cut out family vacations, and in general dropping a wet blanket on any sort of travel. The NASA program took a heavy hit. It could no longer afford manned missions to terrestrial bodies. The last Apollo mission was a link up with a Soviet Soyuz capsule in a rare moment of Cold War cooperation. NASA would have to content itself with satellites like Voyager 1, which was launched into space in 1977.

Truth be told, these satellite missions make much more sense, as the probes could go much further than any manned flight. Voyager 1 is still sending back information from the farthest reaches of our solar system, as it travels at a staggering 60,000 km/hr relative to the sun. No human could have ever survived such a mission.

Still, we crave to go into space, as we saw with the recent missions of Musk, Bezos and Branson. They are already selling space flights and imagine floating space hotels that cling to the safety of earth's gravitational pull. Some companies are even imagining balloon trips into space, recalling Edgar Allen Poe's The Balloon-Hoax.

This dream is fed by science fiction movies, chief among them 2001: A Space Odyssey, based on a novel by Arthur C. Clark. He would serve as one of the principal spokespersons for Apollo missions. Linklater references 2001 in his animated movie but it is hard to imagine a 9 year-old grasping the meaning of this extraordinary story. It took me several tries before I was able to sit through the whole movie as a teenager, and even then I didn't get it. Neither did my Dad, who couldn't figure out why so much time had been spent on apes. I believe it was Kurt Godel who first broached the idea that time can bend back on itself in his famous walk with Einstein. This kind of circular logic essentially suggests a self-perpetuating cosmos that has no need for God, or is in itself God.

When Star Trek first came back to the screen in 1979, it explored the idea of Voyager having made such a rotation and returning to earth in the form of a vast artificial intelligence that called itself V'Ger. The only problem was that it planned to destroy earth. The movie was every bit as slow going as 2001, and not very well received. Here's a trailer for a restored version of the film.

Linklater wisely avoids such an existential theme in his movie, preferring to keep his feature film grounded in space age nostalgia. I recently bought the Dom Architectural Guide Moon, which offers a wonderful collection of images, not just from the US space program, but from the Soyuz program as well. There are also references to the many space fantasies of the era.

However, if man is going to reach the possibly habitable moon Europa, which orbits Jupiter, much less travel beyond our solar system, he will have to do so as a "seed." We simply aren't biologically equipped for space travel, so would have to be transported in vitro to be artificially inseminated upon arrival, and raised by androids until we come of age. Assuming our eggs and sperm could survive such long intergalactic voyages.

This is why Musk's dream to colonize Mars is so absurd. The tremendous amount of cost and time needed to mount such an effort would bankrupt any country, much less corporate billionaire. This also begs to ask that if you can spend this much money on space travel then why not pour that same money into cleaning up our planet? Even at its most vulnerable stage, Earth is far more habitable than Mars or Europa. Like the space race, the conservation movement was born in the 1960s. I collected these stamps too.

Like it or not, we are bound to this planet. We can dream of worlds beyond, which the Egyptians and other early cultures did, but we will never be able to attain them. Only through satellites and space telescopes will we be able to catch a glimpse of the distant reaches of the cosmos. Due to the vast extenuating circumstances of time, only distant images of the past at that. We will not be seeing into the future, as many of these stars have long since burned out, and it is only their afterglow that we see. It is not to say there isn't life on distant planets but we will never know these inhabitants, and so we fantasize them, as science fiction writers have been doing for decades.

Comments

Post a Comment